Inside

|

If you can't grab a bull by its horns, grab its tail

NOFEL WAHID points to the importance of derivative markets in countering financial crises.

What on earth am I talking about? If you are a stock market investor, you know exactly where this is going.

The general outlook for the stock market has improved recently. Investors appear to be a lot more confident with the main index of the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) having crossed the 5,000-point threshold.

Nevertheless, if you ask most investors how they feel about the stock market, many would complain that their money is 'stuck'. They are in the red, and they really have no option but to wait for the market to take off again.

Others were even less fortunate and couldn't afford to wait for the market to turn around. They had to cut their losses and exit the stock market, losing some of their savings in the process.

You often hear finance experts say that those individuals with small amounts of savings and not much staying power should not really invest in the stock market. Apparently, it is too risky for them. Maybe those experts have a point!

However, could it be equally true that small investors have no other option but to invest their savings in the stock market? Let's think about this for a second.

Let's say you are a low-income individual who has Tk 3 lakh in savings. If you deposited that money in a bank in 2011, you would have earned, on average, an interest rate of about 7.2% annually on your deposit. That sounds like a pretty good return, right?

But, what about inflation? With inflation at around 10% in 2011, the real return (meaning adjusted for inflation) on your savings would have actually been negative.

Some would argue that it is possible to get an even higher return on fixed-deposit savings accounts. But let's not forget, -- unlike the stock market, putting money in a fixed-deposit account makes your savings less liquid. So, why shouldn't a low-income investor invest in the stock market?

Of course, investing in the stock market is not without its risks. In which case, the question we really ought to be asking ourselves is -- what can policymakers do to minimise risks for all investors, not just the low-income ones?

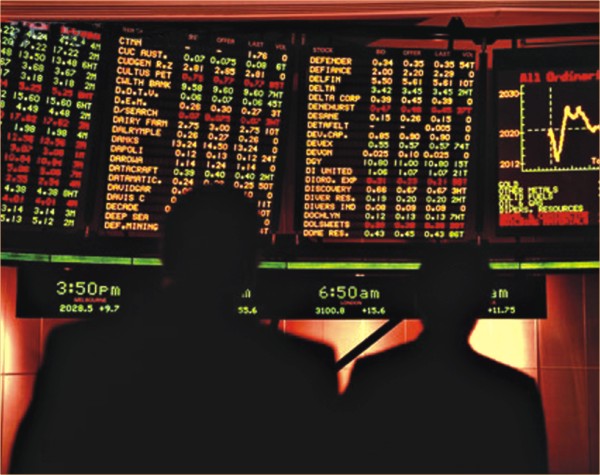

John W Banagan /Getty

John W Banagan /Getty

Fortunately for us, there is actually quite a bit we can do. One such step could be to establish a derivative market, allowing investors to buy 'put options' to minimise the risks associated with a fall in the stock market.

What is a derivative market? And what are put options?

Put simply, a derivative market is where investors can trade financial securities to hedge their risks. A put option is one such type of financial paper, often issued by banks or other financial institutions.

A put option works by giving the buyer of the option the right to sell shares at a pre-determined price. For example, let's say you bought shares in company A for Tk 100. A week later, company A's share price falls to Tk 80. But you happen to have put options on company A's shares, where the pre-determined sale price is Tk 100. Those put options allow you to sell your shares to the bank for Tk 100, thus enabling you to breakeven instead of incurring a loss.

The next obvious question that arises is -- why would a bank issue put options to you? What is in it for the bank?

Banks usually issue these securities for a fee. Let's say that the bank thinks that company A's shares are undervalued and that its share price will likely rise in the next five years. The bank decides to sell you a put option for a fee of Tk 10. If company A's share price does indeed rise over the next five years, the bank profits by pocketing a fee of Tk 10 per option.

Ideally, rational investors would sell their shares before the market price falls below the breakeven cost of Tk 110 (cost of share: TK 100 + cost of option: Tk 10). But if they were unable to do so for whatever reason, investors can at least sell their shares to the bank for Tk 100 and limit their losses to Tk 10 per share, or 9% in the context of this example.

Therein lies the true benefits of establishing a derivative market. It enables investors to limit their losses, and in so doing, helps them develop an understanding of the risk-return trade-off they face.

If you are a low-income investor for whom a 9% loss is too much, regardless of the benefits, then you know you should not invest in the stock market.

Furthermore, the benefits of establishing a derivative market are not just limited to hedging against downside risks. Put options can also be useful tools in preventing unsustainable stock market bubbles from developing in the first place. How?

Let's again go back to our example of company A. Let's assume that company A's share price has doubled in just one month and is currently trading at Tk 200. Market participants are speculating that company A's share price will rise to Tk 500 in the next one year. You have decided that you are going to buy company A's shares to benefit from any possible capital gains.

So you go to the bank and request that they issue a put option to you at the current price of Tk 200. But the bank refuses to issue a put option, or wants to charge some exorbitant fee, such as Tk 100 per option. All because the bank thinks company A's share price is too high and will likely fall.

Remember, -- the bank loses money if the share price falls after issuing a put option. And since a bank has better sources of information and more resources to monitor market developments, the bank is better-positioned to make a judgement on whether share prices are likely to go up or down.

The bank's refusal to issue an option should serve as an important signal to investors and other financial institutions that there is significant uncertainty around company A's future performance. If a majority of investors heed that signal and refrain from buying company A's shares, its share price will not rise unsustainably.

The same principle applies for the market as a whole. If put options for shares in all companies become progressively more expensive over a period of time, it acts as a signal to investors that the market is getting overheated and is due for a correction. And if investors get spooked by that signal and start selling their shares, it prevents a stock market bubble from developing in the first place.

That is what I meant when I said earlier -- grab a bull by its tail.

A well-functioning derivative market can help prevent the formation of a stampeding bull market, which is an invariably superior outcome than for policymakers to have to become matadors and confront raging bull markets head-on.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) tried to play the role of a matador in 2009-10 by tinkering with leverage ratios in its attempt to deflate the stock market bubble. It did not work!

As difficult as that proved for the SEC, it proved nigh impossible for them to awaken the hibernating bear market that followed the crash in late-2010. Even the government, with its myriad policy solutions, was quite helpless in turning the market around for more than a year.

Whether the government's recent announcement of a 50% interest rate waiver for small investors will do the trick, remains to be seen. Even if that policy eventually proves to be successful, it cannot be a permanent solution.

Financial institutions will not, and should not, accept sabotaging their own balance sheets to bailout stock market investors. And if financial institutions do not voluntarily accept the losses to stem from interest rate waivers, the government is hardly in any position to subsidise them. Not when it is running budget deficits that are 5% of GDP.

It is important that the government learns the right lessons from this whole debacle. If the lessons of the global financial crisis are anything to go by, we know that government intervention in financial markets can be very expensive. Throwing good money after bad cannot be the template for fighting future crises.

A cheaper, smarter way of preventing future crises is to undertake structural reforms that address the core causes of a malaise, not its symptoms. In our case, what caused the stock market problem was the bubble that preceded the crash. Derivative markets help prevent the formation of such bubbles. And to the extent that stock markets go up and down, and money is made and lost, a derivative market can also help minimise losses for those who can least afford it.

It is no coincidence that countries like India, Brazil, Mexico and others with increasingly diverse financial market architecture happen to be some of the fastest growing middle-income countries in the world, a distinction we greatly aspire to achieve. Those countries have undertaken significant reforms to promote greater financial inclusion and innovation. It has helped make their financial markets deeper and more liquid, something we need desperately to usher in our next growth spurt.

It is time for us to take a punt on our financial infrastructure! And we, of all people, should not be risk averse about it. Remember the last time we ventured down this path? It revolutionised finance as we knew it and pushed our growth trajectory up a couple of notches.

Nofel Wahid is an applied economist, and can be contacted at wnofel@gmail.com.